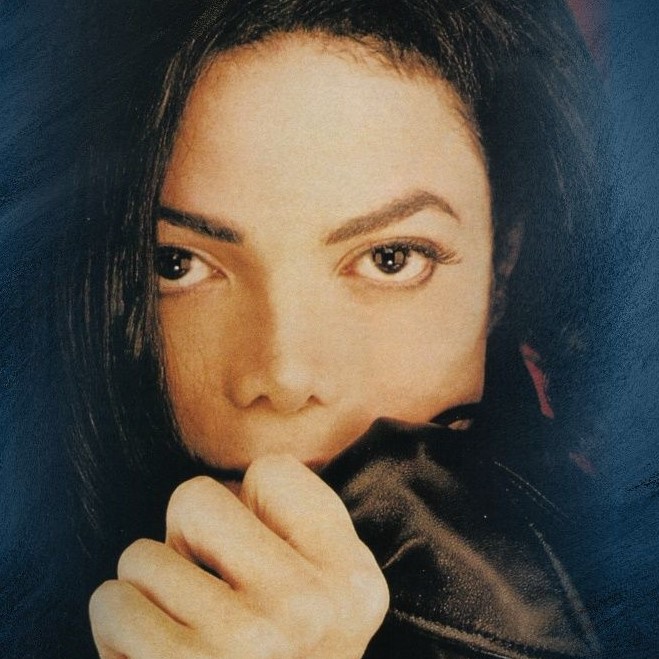

"The King of Pop"

- Group

- Dangerous

- Posts

- 12,784

- Status

- Anonymous

|

|

“BlackorWhite”: come 'Dangerous' ha dato il via al paradosso

della razza di Michael Jackson

Mentre la pelle del Re del Pop diventava più chiara, la sua musica divenne più politicizzata e l'album trascurato del 1991 incapsulò questo momento radicale nella musica.

di Joseph Vogel

Per una figura enigmatica come Michael Jackson, uno dei paradossi più affascinanti della sua carriera è questo: quando è diventato più bianco, è diventato più nero. O per dirla in altro modo: quando la sua pelle divenne più bianca, il suo lavoro divenne più nero.

Per elaborare, dobbiamo riavvolgere una svolta cruciale: i primi anni '90. Con il senno di poi, rappresenta il migliore e il peggiore dei tempi per l'artista. Nel novembre del 1991, Jackson pubblicò il primo singolo dal suo album 'Dangerous': 'Black or White', una fusion pop-rock-rap brillante e accattivante che salì al n. 1 della Billboard Hot 100 e rimase in cima alle classifiche per sei settimane. È stato il suo singolo da solista di maggior successo dopo 'Beat It'.

Il tema di conversazione che circondava Jackson a questo punto, tuttavia, non riguardava la sua musica. Era sulla sua razza. Certo, hanno detto i critici, puoi cantare: 'non importa se sei nero o bianco', ma allora perché si è trasformato in un bianco? Stava sbiancando la sua pelle? Si vergognava di essere nero? Stava cercando di farsi accettare da tutte le razze, trascendendo ogni categoria di identità in uno sforzo vanaglorioso per raggiungere livelli commerciali più alti di 'Thriller'?

Fino ad oggi, molti suppongono che Jackson abbia sbiancato la sua pelle per diventare bianco, che sia stata una decisione cosmetica intenzionale perché si vergognava della sua razza. Eppure a metà degli anni '80 a Jackson è stata diagnosticata la vitiligine, un disturbo cutaneo che causa la perdita di pigmentazione della pelle. Secondo quelli a lui più vicino, è stata una sfida personale terribilmente umiliante, in cui ha fatto di tutto per nasconderla con camicie a maniche lunghe, cappelli, guanti, occhiali da sole e maschere. Quando Jackson morì nel 2009, la sua autopsia confermò definitivamente che aveva la vitiligine, così come diceva la sua storia medica.

Tuttavia, all'inizio degli anni '90, il pubblico era scettico a dir poco. Jackson ha rivelato pubblicamente di avere la vitiligine in un'intervista del 1993 ampiamente vista con Oprah Winfrey. "Questa è la situazione", ha spiegato. "Ho una malattia che distrugge la pigmentazione della pelle. Non posso farci niente, ok? Ma quando le persone inventano storie che non voglio essere quello che sono mi fa male ... È un problema per me e che non riesco a controllare. "

Jackson ha ammesso di aver fatto interventi di chirurgia plastica ma ha detto di essere "innorridito” dal giudizio della gente che lo considerava uno che non voleva essere nero. "Sono un americano nero", dichiarò. "Sono orgoglioso della mia razza”. Sono orgoglioso di quello che sono. "

Per Jackson, quindi, non c'era alcuna ambivalenza sulla sua identità e eredità razziale. La sua pelle era cambiata ma la sua razza no. In realtà, semmai, la sua identificazione come artista nero era diventata più forte. Il primo indizio è arrivato con il video di 'Black or White'. Visto da un pubblico mondiale senza precedenti, 500 milioni di telespettatori, è stata la più grande piattaforma di Jackson di sempre; una piattaforma, va detto, che si era guadagnato abbattendo le barriere razziali su MTV con i suoi cortometraggi rivoluzionari di 'Thriller'.

I primi minuti del video di 'Black or White' sembravano relativamente benigni e coerenti con gli utopici messaggi di canzoni precedenti (Can You Feel It, We Are the World, Man in the Mirror). Jackson, vestito con abiti in cui contrastavano il nero eil bianco, viaggia attraverso il globo, adattando fluidamente i suoi passi di danza a qualunque cultura o paese in cui si trovi.

Agisce come una sorta di sciamano cosmopolita, esibendosi al fianco di africani, nativi americani, thailandesi, indiani e russi, tentando, sembra, di istruire il White American Father (Padre Americano Bianco, interpretato da George Wendt) sulle bellezze della differenza e della diversità. La parte principale del video culmina con la rivoluzionaria "sequenza di morphing", in cui le facce esuberanti di varie razze si fondono perfettamente tra loro. Il messaggio trasmesso è : facciamo tutti parte della famiglia umana - distinta ma connessa - indipendentemente dalle variazioni estetiche.

Nell'erà di Trump e della rinascita del nazionalismo bianco, anche quel messaggio multiculturale rimane vitale. Ma non è tutto ciò che Jackson ha da dire. Proprio quando il regista (John Landis) urla 'Taglia!' vediamo una pantera nera che esce fuori dal set e si dirige verso un vicolo.

Ciò che avviene dopo è diventata la mossa artistica più rischiosa di Jackson fino a questo punto della sua carriera, in particolare considerando le aspettative del suo pubblico "adatto alle famiglie". In contrasto con il tono allegro, per lo più ottimistico della parte principale del video, Jackson scatena una raffica di rabbia sfrenata, dolore e aggressività. Fracassa una macchina con un piede di porco, si tocca, si strofina, grugnisce e urla, getta un bidone della spazzatura in un negozio (riecheggiando il controverso climax del film di Spike Lee del 1989, 'Do the Right Thing'), prima di cadere in ginocchio e strapparsi la camicia. Il video termina con Homer Simpson, un altro padre americano bianco, che prende il telecomando da suo figlio, Bart, e spegne la TV. Quella mossa di disapprovazione si è dimostrata preveggente.

La cosiddetta “panther dance” provocò un putiferio; molto più, per ironia della sorte, di qualsiasi cosa fosse stata pubblicata quell'anno dai Nirvana o dai Guns N 'Roses. Fox, la stazione americana che in origine trasmetteva il video, fu bombardata da lamentele. In una storia di prima pagina, Entertainment Weekly l'ha descrisse come "Il video incubo di Michael Jackson". Alla fine, cedendo alla pressione, Fox e MTV eliminarono gli ultimi quattro minuti del video.

Tuttavia, in mezzo alle polemiche (la maggior parte dei media l'ha semplicemente liquidata come una "trovata pubblicitaria"), in pochissimi si sono posti la semplice domanda: cosa significava? Bloccato tra le percosse a Rodney King e le rivolte di Los Angeles, sembra assurdo, a prima vista, non interpretare il cortometraggio in quel contesto. Le tensioni razziali negli Stati Uniti, in particolare a Los Angeles, erano incandescenti,

In questo clima, Michael Jackson - il più famoso intrattenitore nero del mondo - ha realizzato un cortometraggio in cui sfugge ai confini del palcoscenico di Hollywood, si trasforma in una pantera nera e incanala la rabbia repressa e l'indignazione di una nazione e di un particolare momento. Lo stesso Jackson in seguito ha spiegato che nel finale del videoclip voleva "fare un numero di danza in cui potevo esprimere la mia frustrazione sull'ingiustizia e sui pregiudizi, sul razzismo e il fanatismo, e durante la danza mi sono arrabbiato e lasciato andare".

Il cortometraggio 'Black or White' non era un'anomalia nella sua messaggistica razziale. L'album 'Dangerous', dalle sue canzoni ai suoi cortometraggi, non solo mette in risalto il talento, gli stili e i suoni del nero, ma funge anche come una sorta di tributo alla cultura nera. Forse l'esempio più ovvio di questo è il video di 'Remember the Time'. Con alcuni dei più importanti personaggi di colore dell'epoca - Magic Johnson, Eddie Murphy e Iman - il video è ambientato nell'antico Egitto. In contrasto con le rappresentazioni stereotipate di Hollywood degli afroamericani come servi, Jackson li presenta qui con regalità.

Promesso un budget di produzione considerevole, Jackson ha arruolato John Singleton, un giovane regista nero emergente che ha ottenuto il successo di Boyz N the Hood, per il quale ha ricevuto una nomination all'Oscar. La collaborazione di Jackson e Singleton ha dato vita a uno dei video musicali più lussuosi e memorabili della sua carriera, evidenziato dalla complessa sequenza di danza hip-hop geroglifica (coreografata da Fatima Robinson). Ancora una volta, Jackson è apparso più bianco che mai, ma il video - diretto, coreografato e interpretato da talenti neri - era una celebrazione della storia, dell'arte e della bellezza nera.

La canzone, infatti, è stata prodotta e co-scritta da un'altra giovane stella nascente nera, Teddy Riley, l'architetto del nuovo jack swing. Prima di Riley, Jackson aveva contattato una serie di altri artisti e produttori neri, tra cui LA Reid, Babyface, Bryan Loren e LL Cool J, alla ricerca di qualcuno con cui poter sviluppare un nuovo suono post-Quincy Jones. Trovò quello che stava cercando in Riley, i cui ritmi contenevano il pugno dell'hip-hop, l'oscillazione del jazz e gli accordi della chiesa nera. 'Remember the Time' è forse la loro collaborazione più nota, con il suo caldo fondo d'organo e il ritmo serrato della batteria. È diventato un grande successo per la radio nera e ha raggiunto il numero 1 nella classifica R & B / hip-hop di Billboard.

Le prime sei tracce di 'Dangerous' sono collaborazioni Jackson-Riley. Non sembravano niente che Jackson avesse mai fatto prima, dal vetro in frantumi e il suono metallico di 'Jam' al funk industriale funk del titolo dell'album. Invece dell'eccellente R & B di 'Thriller' e del dramma cinematografico di 'Bad', c'è un messaggio più crudo, urgente e in sintonia con le strade. In 'She Drives Me Wild', l'artista costruisce una canzone completa intorno ai suoni della strada: motori, clacson, porte che sbattono e sirene. In molte altre canzoni Jackson integra il rap, uno dei primi artisti pop - insieme a Prince - a farlo.

'Dangerous' è diventato l'album più venduto da Jackson dopo 'Thriller', con 7 milioni di copie vendute negli Stati Uniti e oltre 32 milioni di copie in tutto il mondo. Eppure, al momento, molti lo consideravano l'ultimo disperato tentativo di Jackson di reclamare il suo trono Quando 'Nirvana's Nevermind' sostituì 'Dangerous' in cima alle classifiche nella seconda settimana di gennaio del 1992, i critici del rock bianco dichiararono allegramente che il regno del Re del Pop era finito.

È facile vedere il simbolismo di quel momento. Tuttavia, 'Dangerous' è invecchiato bene. Tornando ad esso ora, senza l'esagerazione o i pregiudizi che hanno accompagnato il suo rilascio nei primi anni '90, si ha un senso più chiaro del suo significato. Come 'Nevermind', ha sondato la scena culturale - e l'angoscia interna del suo creatore - in modo convincente.

Inoltre, si potrebbe sostenere che 'Dangerous' è stato altrettanto significativo per la trasformazione della musica nera (R & B / new jack swing) come 'Nevermind' lo è stato per la musica bianca (alternativa / grunge). La scena musicale contemporanea è sicuramente molto più debitrice nei confronti di 'Dangerous' (es. 'Finesse', il recente nuovo singolo rilasciato da Bruno Mars e Cardi B).

Solo di recente i critici hanno iniziato a rivalutare il significato di 'Dangerous'. In un articolo del 2009 pubblicato da The Guardian, viene definito come il 'vero culmine della carriera' di Jackson.

Nel suo libro sull'album della serie Bloomsbury’s 33 ⅓ , Susan Fast descrive 'Dangerous' come l'album “della maggiore età” dell'artista. Il disco, scrive, “ 'offre un Jackson sulla soglia che finalmente arriva ad abitare nella sua età adulta - non è questo che mancava così tanto a qualcuno? - e facendolo attraverso un'immersione nella musica nera che continuerà solo ad approfondire la sua opera successiva ".

Quell'immersione continuò anche nel suo lavoro visivo, che, oltre a 'Black or White' e 'Remember the Time', mostrò l'elegante atletismo della superstar del basket Michael Jordan nel video musicale di 'Jam' e la palpabile sensualità di Naomi Campbell nel cortometraggio color seppia di 'In the Closet'.

Qualche anno più tardi, ha lavorato con Spike Lee nella parte più razziale della sua carriera, 'They Do not Care About Us', che è stato resuscitato come inno per il movimento “Black Lives Matter”. Eppure, critici, comici e pubblico hanno continuato a suggerire che Jackson si vergognasse della sua razza.

E' diventata una battuta comune: 'Solo in America un povero bambino nero può diventare una ricca donna bianca'.

Eppure Jackson ha dimostrato che la razza è qualcosa di più della mera pigmentazione o delle caratteristiche fisiche. Mentre la sua pelle diventava più bianca, il suo lavoro negli anni '90 non è mai stato più ricco di orgoglio, talento, ispirazione e cultura nera.

Traduzione: MJGOLDWORLD

|

|

Contacts

Contacts