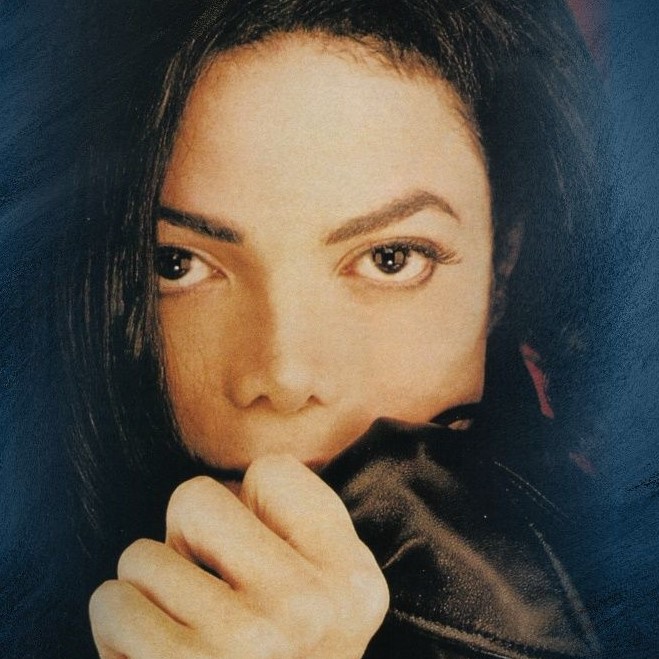

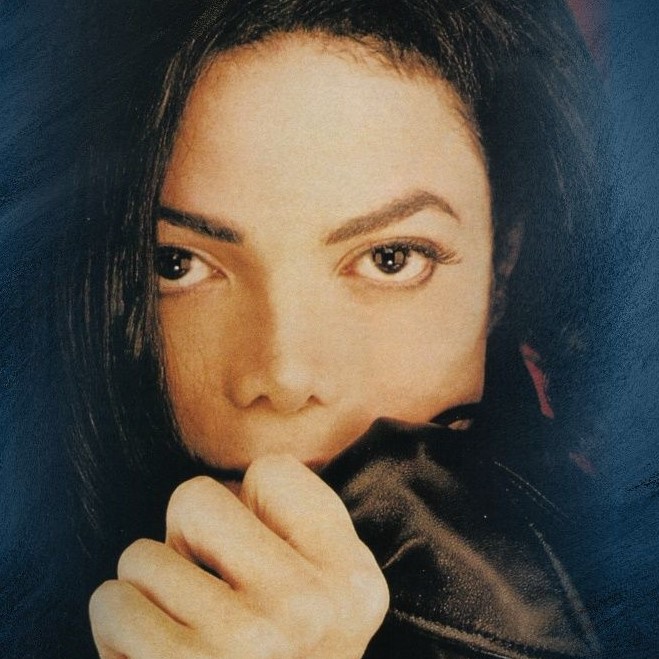

"The King of Pop"

- Group

- Dangerous

- Posts

- 12,784

- Status

- Anonymous

|

|

-------------------------------------

Nel corso dei mesi, da entrambe le parti furono assunti, degradati e sostituiti avvocati che si contendevano le migliori strategie. Rothman smise di essere l'avvocato di Chandler alla fine di Agosto, quando la parte di Jackson denunciò entrambi per tentativo di estorsione. Ed entrambi assunsero degli avvocati penali fra i più pagati che li rappresentassero. Rothman impiegò Robert Shapiro, l’attuale avvocato di O.J. Simpson. Secondo il diario dell'ex collega di Rothman, il 26 Agosto, prima che fossero avanzate le accuse del tentativo di estorsione, a Chandler fu sentito dire: "E' il mio culo che corre il pericolo di andare in prigione".

Le investigazioni sulle estorsioni furono superficiali, rivela una fonte , perchè "la polizia non le ha mai prese sul serio.”

Ma si sarebbe potuto fare molto di più." Per esempio, la polizia, come aveva fatto con Jackson, avrebbe potuto richiedere dei mandati di perquisizione degli uffici e le case di Rothman e Clìandler . E quando entrambi, tramite i loro avvocati ,si rifiutarono di essere interrogati dalla polizia, si sarebbe potuto convocare un Gran Jury.

A metà Settembre, Larry Feldman un'avvocato civile che era stato capo dell'associazione degli avvocati di Los Angeles, incominciò a rappresentare il figlio di Chandler e immediatamente prese il controllo delle situazione. Intentò una causa civile contro Jackson, la quale potrebbe essere vista come l'inizio della fine.

Una volta sparsa la notizia della causa, i lupi si stavano preparando ad attaccare. Secondo un membro del team legale di Jackson "Feldman ricevette dozzine di lettere da parte di gente di tutti i tipi che dicevano di essere state molestate da Jackson. Le hanno esaminate tutte per trovare qualcuna e ne hanno trovate zero.

Con la possibilità, ora, che accuse criminali potessero delinearsi contro Jackson, Bertfield assunse Howard Weitzman , un famoso avvocato penale con una catena di clienti di elevata immagine incluso John De Lorean, del quale vinse la causa, e Kim Basinger, della quale perse la causa per il contratto "Boxing Helena" . Weitzman è stato anche, per un breve periodo, avvocato di O.J. Simpson. Alcuni avevano predetto problemi fra i due avvocati sin dal 'inizio. Non vi era una stanza che potesse ospitare due avvocati così fortemente abituati a condurre i propri shows da soli.

Dal giorno in cui Weitzman si unì al team di difesa di Jackson, "Parlava sempre di un accordo", dice Bonnie Ezkenazi , un'avvocato che lavorava per la difesa. Fields e Pellicano ancora al controllo della difesa di Jackson, adottarono una strategia aggressiva . Credevano fermamente nell'innocenza di Jackson e giurarono di combattere le accuse in corte. Pellicano iniziò a raccogliere prove da usare durante il processo , che era stato fissato per il 21 Marzo 1994. "Avevano una causa che proprio non reggeva" , dice Fields."Volevano combattere. Michael voleva combattere e affrontare il processo . “Sentivamo di poter vincere."

I disaccordi all'interno del clan di Jackson crebbero il 21 Novembre , dopo che il pubblicista di Jackson ebbe annunciato, durante una conferenza stampa , che il cantante avrebbe cancellato le successive date del suo World Tour per sottoporsi ad un programma di riablitazione per trattare la sua dipendenza da farmaci.

Più tardi, Fields disse ai giornalisti che Jackson era a malapena capace di ragionare adeguatamente a livello intellettivo. Altri del clan Jackson, credevano che fosse un errore descrivere il cantante come un'incapace "Era importante”, dice Fields, "dire la verità,” Larry Feldman e la stampa credevano che Michael stesse cercando di nascondersi e che fosse tutto falso.

Ma non lo era.

" Il 23 Novembre l'attrito raggiunse l'apice. Basandosi su delle informazioni che disse di aver ricevuto da Weitzman , Fields disse in una sala del tribunale piena di giornalisti che un atto

d 'accusa penale contro Jackson sembrava imminente. Fields aveva una ragione per fare tale dichiarazione, stava cercando di ritardare la causa civile provando che vi era un' incombente processo penale che doveva essere fatto prima. Fuori dalla sala i giornalisti chiesero a Fields perchè avesse fatto un'annuncio al quale Weitzrnan aveva risposto essenzialmente che Fields "lo aveva nominato erroneamente". Il commento, infuriò Fields "perchè non era vero" , dice. "E' stato nient'altro che un oltraggio. Ero molto adirato con Howard". La settimana successiva Fields mandò a Jackson una lettera di dimissioni ."C'era tutta quella gente che voleva fare tante cose diverse, e prendere una decisione era come muoversi in una melassa" , spiega Fields. "Era un incubo, e voleva uscire da quell'inferno". Pellicano, che aveva ricevuto la sua dose di rimproveri per il suo comportamento aggressivo, si dimise nello stesso periodo.

Con Fields e Pellicano fuori dai giochi, Weitzman assunse Johnnie Cochran Jr., un' avvocato civile abbastanza conosciuto che stava aiutando la difesa di O.J.Simpson, w John Branca, che nel 1990 era stato sostituito da Fields come avvocato generale, tornò nel consiglio. Alla fine del1993, quando il DA di entrambe le contee di Santa Barbara e Los Angeles convocarono il Grand Jury per decidere se dovessero essere passate agli atti le accuse penali contro Jackson o no, la strategia della difesa cambiò corso e le chiacchiere di un accordo civile divennero realtà , sebbene anche il suo nuovo team credesse nell 'innocenza di Jackson.

Perché la difesa di Jackson ha accettato un accordo in via extragiudiziale nonostante le dichiarazioni di innocenza e le prove discutibili contro di lui?

I suoi avvocati apparentemente decisero che c'erano troppi fattori che mettevano in discussione il fatto di portare il caso nella corte civile. Fra questi vi era il fatto che la fragilità emotiva di Jackson sarebbe stata messa a dura prova dall'oppressività dei media che avrebbero con piacere tormentato il cantante giorno dopo giorno nel corso di un processo che sarebbe potuto durare anche sei mesi.

Questioni razziali e politiche sarebbero filtrate nei procedimenti legali in particolar modo a Los Angeles , che ancora doveva riprendersi dal caso Rodney King e la difesa temeva che una corte di giustizia non avrebbe potuto fare giustizia.

Come fatto da considerare c’era da aggiungere che la giuria era una miscela di razze. Come ci dice un 'avvocato, "calcolarono che gli ispanici si sarebbero risentiti con Jackson per il suo denaro, i neri per aver cercato di essere bianco e i bianchi si sarebbero creati dei problemi per il caso di molestie".

Secondo Resnick. “ C'è tanta isteria e lo stigma delle molestie su minori è così forte che non c’è modo di difendersi".

Gli avvocati di Jackson erano anche preoccupati su cosa sarebbe potuto succedere se fosse seguito un processo penale, particolarmente a Santa Barbara che è una comunità formata in maggioranza da bianchi, conservatori e di ceto medio superiore. In qualsiasi modo lo si guardasse, "un processo civile appariva troppo rischioso. Di fronte ai termini dell'accordo civile, alcune fonti dicono, gli avvocati reputavano che avrebbero potuto anticipare il processo penale lasciando sottintendere che Chandler sarebbe stato d'accordo a non fare testimoniare il figlio.

Altri vicini al caso dicono che la decisione di un'accordo ha probabilmente avuto a che fare con un altro fattore: la reputazione degli avvocati. "Potete immaginare cosa sarebbe successo ad un avvocato che perde la causa di Michael Jackson? " dice Anthony Pellicano. " Per i tre avvocati non c’è modo che ne possano uscire vincitori, a meno che non facciano un 'accordo.”

“L'unica persona che ha perso è Michael Jackson". Ma Jackson, dice Branca " ha cambiato idea sul fatto di affrontare un processo quando è tornato in questo paese. Non aveva visto tutti giornali e non sapeva quanto gli fossero ostili . Voleva solo che tutto finisse"

Dall'altra parte, le relazioni fra i membri della famiglia del ragazzo si erano fatte sgradevoli. Durante un'incontro nello studio di Larry Feldman verso la fine del '93, Chandler, rivela una fonte, perse completamente il controllo e picchiò Dave Schwartz che, separatosi da June in seguito a tale episodio, veniva spinto a prendere decisioni che riguardavano il figliastro, ed era risentito con Chandler per essersi preso il ragazzo e non avergli permesso di ritornare con loro.

Dave [Schwartz] s'infuriò e disse ad Evan che si trattava comunque di estorsione e a quel punto Evan si alzò, si avvicinò a Dave ed iniziò a picchiarlo", dice un altra fonte.

Per chiunque vivesse a Los Angeles nel Gennaio del 1994, c'erano due questioni principali sulle quali discutere: il terremoto e l'accordo di Jackson . Il 25 Gennaio, Jackson accettò di pagare al ragazzo una somma mai rivelata . Il giorno prima gli avvocati di Jackson avevano ritirato le accuse di estorsione contro Chandler e Rothman.

IL vero ammontare dell’accordo non è mai stato rivelato, ma secondo alcune indiscrezioni sarebbe di 20 milioni di dollari. Una fonte dice che Chandler e June Schwartz avrebbero ricevuto due milioni di dollari ciascuno, mentre l'avvocato Feldman avrebbe ottenuto il 25% in beni di contingenza. Il resto del denaro è stato vincolato in amministrazioni fiduciari per il ragazzo e sarà pagata sotto la supervisione di un'amministratore fiduciario assegnato dalla corte stessa.

"Non bisogna dimenticare che questo caso è stato solo di denaro," dice Pellicano , ed Evan Chandler se l'è cavata ottenendo ciò che desiderava. " Dato che Chandler ha ancora la custodia del figlio, alcune fonti sostengono che logicamente ciò significa che il padre ha accesso a qualsiasi somma di denaro che il figlio riceve.

Alla fine del maggio del '94, Chandler infine sembra aver definitivamente lasciato l'ambiente dentistico. Aveva chiuso il suo studio di Beverly Hills, citando le molestie in corso da parte dei sostenitori di Jackson. Secondo i termini dell’accordo, a Chandler è apparentemente vietato scrivere qualsiasi cosa sull'affare, ma si dice che suo fratello, Roy Chandler stesse cercando di ottenere un contratto editoriale.

In quello che potrebbe rivelarsi il caso infinito, lo scorso agosto, sia Barry Rothman e Dave Schwartz (due principali elementi lasciati fuori dell'accordo) hanno denunciato civilmente Jackson. Schwartz sostiene che il cantante è colpevole di aver distrutto la sua famiglia.

La querela di Rothman sostiene sia la diffamazione e calunnia da parte di Jackson e sia l'accusa di un tentativo di estorsione da parte del team di difesa - Fields, Pellicallo e Weitzman . "l'accusa di estorsione" dice l 'avvocato di Rothman, Aitken , "è completamente falsa. Mr. Rothman è stato pubblicamente preso in giro, è stato materia d'investigazioni penali ed ha subito una perdita di reddito".

Presumibilmente parte del denaro perso da Rothman è la considerevole somma che avrebbe intascato se fosse stato ancora l'avvocato di Chandler nella fase dell'accordo.

Per quanto riguarda Michael Jackson, "Sta andando avanti con la sua vita", dice il pubblicista Michael Levine. Ora, sposato, Jackson ha recentemente registrato tre nuove canzoni per il “Greatest Hits” e completato un nuovo video musicale dal titolo "History “.

E che ne è stato delle massicce investigazioni su Jackson?.

Dopo milioni di dollari spesi dai procuratori e dai dipartimenti di polizia in due giurisdizioni, e dopo gli interrogatori da parte di due Grand Jury a duecento testimoni, inclusi trenta bambini conoscenti di Jackson, non è stato trovato un solo testimone che convalidasse le accuse.

(Nel Giugno 1994, ancora determinanti a trovarne almeno uno, tre procuratori e due detective della polizia sono volati in Australia per interrogare Wade Robson, il ragazzo che aveva ammesso di aver dormito nello stesso letto con Jackson . Ancora una volta, il ragazzo ha detto che non è accaduto niente di male.)

L'unica accusa sollevata a Jackson, allora, rimane quella di un giovane, Jordan Chandler, e solo dopo che al ragazzo è stata somministrata una potente droga ipnotica che lo rende suscettibile al potere della suggestione.

"Trovo questo caso molto sospetto," dice il Dottor Underwager, uno psichiatra di Minneapolis, "soprattutto perchè l'unica ci viene dal ragazzo, la quale sarebbe improbabile."

"I veri pedofili hanno una media di duecentoquaranta vittime nel corso della loro vita. E' un disturbo progressivo.Non sono mai soddisfatti. Date le insufficienti prove contro Jackson, sembra improbabile che sarebbe stato riconosciuto colpevole se il caso si fosse concluso con un processo."

"Ma nella corte dell'opinione pubblica, non esistono limiti.

La gente è libera di speculare come preferisce e l'eccentricità di Jackson lo rende vulnerabile alla probabilità che il pubblico pensi male di lui."

Allora, non è forse possibile che Jackson non abbia commesso alcun crimine e che sia ciò che ha sempre detto "di essere, un non molestatore, ma un protettore dei bambini?

L'avvocato Michael Freeman la pensa così: "Penso che Jackson non abbia fatto niente di male e che queste persone [Chandler e Rothrman] abbiano visto un'opportunità e programmato tutto.

Credo che sia solo una questione di denaro".

Per alcuni osservatori, la storia di Michael Jackson mostra quanto il potere delle accuse sia pericoloso, contro il quale spesso non c'è difesa - soprattutto quando le accuse riguardano abusi sessuali su minori.

Per altri c'è qualcos'altro che ora è più chiaro -- la polizia e i procuratori hanno speso milioni di dollari per creare un caso le cui fondamenta non sono mai esistite.

[ Non è stata trovata alcuna prova contro Michael Jackson, Chandler accusò Jackson solo per estorcergli denaro. ]

Mary A. Fischer è una scrittrice senior di GQ con sede a Los Angeles.

----------------------------------------------------

Source: http://prince.org/msg/8/70096?pr // Testo in Italiano: http://mjirda.altervista.org/GQ.htm

****************************************

ORIGINAL TEXT

'Was Michael Jackson Framed?' (GQ ARTICLE 1994)

Was Michael Jackson Framed? The Untold Story

By Mary A. Fisher (GQ, October 1994)

The untold story of the events that brought down a superstar.

Before O.J. Simpson, there was Michael Jackson -- another beloved black

celebrity seemingly brought down by allegations of scandal in his

personal life. Those allegations -- that Jackson had molested a

13-year-old boy -- instigated a multimillion-dollar lawsuit, two

grand-jury investigations and a shameless media circus. Jackson, in

turn, filed charges of extortion against some of his accusers.

Ultimately, the suit was settled out of court for a sum that has been

estimated at $20 million; no criminal charges were brought against

Jackson by the police or the grand juries. This past August, Jackson

was in the news again, when Lisa Marie Presley, Elvis's daughter,

announced that she and the singer had married.

As the dust settles on one of the nation's worst episodes of media

excess, one thing is clear: The American public has never heard a

defense of Michael Jackson. Until now.

It is, of course, impossible to prove a negative -- that is, prove

that something didn't happen. But it is possible to take an in-depth

look at the people who made the allegations against Jackson and thus

gain insight into their character and motives. What emerges from such

an examination, based on court documents, business records and scores

of interviews, is a persuasive argument that Jackson molested no one

and that he himself may have been the victim of a well-conceived plan

to extract money from him.

More than that, the story that arises from this previously unexplored

territory is radically different from the tale that has been promoted

by tabloid and even mainstream journalists. It is a story of greed,

ambition, misconceptions on the part of police and prosecutors, a lazy

and sensation-seeking media and the use of a powerful, hypnotic drug.

It may also be a story about how a case was simply invented.

Neither Michael Jackson nor his current defense attorneys agreed to be

interviewed for this article. Had they decided to fight the civil

charges and go to trial, what follows might have served as the core of

Jackson's defense -- as well as the basis to further the extortion

charges against his own accusers, which could well have exonerated the

singer.

Jackson's troubles began when his van broke down on Wilshire Boulevard

in Los Angeles in May 1992. Stranded in the middle of the heavily

trafficked street, Jackson was spotted by the wife of Mel Green, an

employee at Rent-a-Wreck, an offbeat car-rental agency a mile away.

Green went to the rescue. When Dave Schwartz, the owner of the

car-rental company, heard Green was bringing Jackson to the lot, he

called his wife, June, and told her to come over with their 6-year-old

daughter and her son from her previous marriage. The boy, then 12, was

a big Jackson fan. Upon arriving, June Chandler Schwartz told Jackson

about the time her son had sent him a drawing after the singer's hair

caught on fire during the filming of a Pepsi commercial. Then she gave

Jackson their home number.

"It was almost like she was forcing [the boy] on him," Green recalls.

"I think Michael thought he owed the boy something, and that's when it

all started."

Certain facts about the relationship are not in dispute. Jackson began

calling the boy, and a friendship developed. After Jackson returned

from a promotional tour, three months later, June Chandler Schwartz

and her son and daughter became regular guests at Neverland, Jackson's

ranch in Santa Barbara County. During the following year, Jackson

showered the boy and his family with attention and gifts, including

video games, watches, an after-hours shopping spree at Toys "R" Us and

trips around the world -- from Las Vegas and Disney World to Monaco

and Paris.

By March 1993, Jackson and the boy were together frequently and the

sleepovers began. June Chandler Schwartz had also become close to

Jackson "and liked him enormously," one friend says. "He was the

kindest man she had ever met."

Jackson's personal eccentricities -- from his attempts to remake his

face through plastic surgery to his preference for the company of

children -- have been widely reported. And while it may be unusual for

a 35-year-old man to have sleepovers with a 13-year-old child, the

boy's mother and others close to Jackson never thought it odd.

Jackson's behavior is better understood once it's put in the context

of his own childhood.

"Contrary to what you might think, Michael's life hasn't been a walk

in the park," one of his attorneys says. Jackson's childhood

essentially stopped -- and his unorthodox life began -- when he was 5

years old and living in Gary, Indiana. Michael spent his youth in

rehearsal studios, on stages performing before millions of strangers

and sleeping in an endless string of hotel rooms. Except for his eight

brothers and sisters, Jackson was surrounded by adults who pushed him

relentlessly, particularly his father, Joe Jackson -- a strict,

unaffectionate man who reportedly beat his children.

Jackson's early experiences translated into a kind of arrested

development, many say, and he became a child in a man's body. "He

never had a childhood," says Bert Fields, a former attorney of

Jackson's. "He is having one now. His buddies are 12-year-old kids.

They have pillow fights and food fights." Jackson's interest in

children also translated into humanitarian efforts. Over the years, he

has given millions to causes benefiting children, including his own

Heal The World Foundation.

But there is another context -- the one having to do with the times in

which we live -- in which most observers would evaluate Jackson's

behavior. "Given the current confusion and hysteria over child sexual

abuse," says Dr. Phillip Resnick, a noted Cleveland psychiatrist, "any

physical or nurturing contact with a child may be seen as suspicious,

and the adult could well be accused of sexual misconduct."

Jackson's involvement with the boy was welcomed, at first, by all the

adults in the youth's life -- his mother, his stepfather and even his

biological father, Evan Chandler (who also declined to be interviewed

for this article). Born Evan Robert Charmatz in the Bronx in 1944,

Chandler had reluctantly followed in the footsteps of his father and

brothers and become a dentist. "He hated being a dentist," a family

friend says. "He always wanted to be a writer." After moving in 1973

to West Palm Beach to practice dentistry, he changed his last name,

believing Charmatz was "too Jewish-sounding," says a former colleague.

Hoping somehow to become a screenwriter, Chandler moved to Los Angeles

in the late Seventies with his wife, June Wong, an attractive Eurasian

who had worked briefly as a model.

Chandler's dental career had its precarious moments. In December 1978,

while working at the Crenshaw Family Dental Center, a clinic in a

low-income area of L.A., Chandler did restoration work on sixteen of a

patient's teeth during a single visit. An examination of the work, the

Board of Dental Examiners concluded, revealed "gross ignorance and/or

inefficiency" in his profession. The board revoked his license;

however, the revocation was stayed, and the board instead suspended

him for ninety days and placed him on probation for two and a half

years. Devastated, Chandler left town for New York. He wrote a film

script but couldn't sell it.

Months later, Chandler returned to L.A. with his wife and held a

series of dentistry jobs. By 1980, when their son was born, the

couple's marriage was in trouble. "One of the reasons June left Evan

was because of his temper," a family friend says. They divorced in

1985. The court awarded sole custody of the boy to his mother and

ordered Chandler to pay $500 a month in child support, but a review of

documents reveals that in 1993, when the Jackson scandal broke,

Chandler owed his ex-wife $68,000 -- a debt she ultimately forgave.

A year before Jackson came into his son's life, Chandler had a second

serious professional problem. One of his patients, a model, sued him

for dental negligence after he did restoration work on some of her

teeth. Chandler claimed that the woman had signed a consent form in

which she'd acknowledged the risks involved. But when Edwin Zinman,

her attorney, asked to see the original records, Chandler said they

had been stolen from the trunk of his Jaguar. He provided a duplicate

set. Zinman, suspicious, was unable to verify the authenticity of the

records. "What an extraordinary coincidence that they were stolen,"

Zinman says now. "That's like saying 'The dog ate my homework.' " The

suit was eventually settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.

Despite such setbacks, Chandler by then had a successful practice in

Beverly Hills. And he got his first break in Hollywood in 1992, when

he cowrote the Mel Brooks film Robin Hood: Men in Tights. Until

Michael Jackson entered his son's life, Chandler hadn't shown all that

much interest in the boy. "He kept promising to buy him a computer so

they could work on scripts together, but he never did," says Michael

Freeman, formerly an attorney for June Chandler Schwartz. Chandler's

dental practice kept him busy, and he had started a new family by

then, with two small children by his second wife, a corporate

attorney.

At first, Chandler welcomed and encouraged his son's relationship with

Michael Jackson, bragging about it to friends and associates. When

Jackson and the boy stayed with Chandler during May 1993, Chandler

urged the entertainer to spend more time with his son at his house.

According to sources, Chandler even suggested that Jackson build an

addition onto the house so the singer could stay there. After calling

the zoning department and discovering it couldn't be done, Chandler

made another suggestion -- that Jackson just build him a new home.

That same month, the boy, his mother and Jackson flew to Monaco for

the World Music Awards. "Evan began to get jealous of the involvement

and felt left out," Freeman says. Upon their return, Jackson and the

boy again stayed with Chandler, which pleased him -- a five-day visit,

during which they slept in a room with the youth's half brother.

Though Chandler has admitted that Jackson and the boy always had their

clothes on whenever he saw them in bed together, he claimed that it

was during this time that his suspicions of sexual misconduct were

triggered. At no time has Chandler claimed to have witnessed any

sexual misconduct on Jackson's part.

Chandler became increasingly volatile, making threats that alienated

Jackson, Dave Schwartz and June Chandler Schwartz. In early July 1993,

Dave Schwartz, who had been friendly with Chandler, secretly

tape-recorded a lengthy telephone conversation he had with him. During

the conversation, Chandler talked of his concern for his son and his

anger at Jackson and at his ex-wife, whom he described as "cold and

heartless." When Chandler tried to "get her attention" to discuss his

suspicions about Jackson, he says on the tape, she told him "Go fuck

yourself."

"I had a good communication with Michael," Chandler told Schwartz. "We

were friends. I liked him and I respected him and everything else for

what he is. There was no reason why he had to stop calling me. I sat

in the room one day and talked to Michael and told him exactly what I

want out of this whole relationship. What I want."

Admitting to Schwartz that he had "been rehearsed" about what to say

and what not to say, Chandler never mentioned money during their

conversation. When Schwartz asked what Jackson had done that made

Chandler so upset, Chandler alleged only that "he broke up the family.

[The boy] has been seduced by this guy's power and money." Both men

repeatedly berated themselves as poor fathers to the boy.

Elsewhere on the tape, Chandler indicated he was prepared to move

against Jackson: "It's already set," Chandler told Schwartz. "There

are other people involved that are waiting for my phone call that are

in certain positions. I've paid them to do it. Everything's going

according to a certain plan that isn't just mine. Once I make that

phone call, this guy [his attorney, Barry K. Rothman, presumably] is

going to destroy everybody in sight in any devious, nasty, cruel way

that he can do it. And I've given him full authority to do that."

Chandler then predicted what would, in fact, transpire six weeks

later: "And if I go through with this, I win big-time. There's no way

I lose. I've checked that inside out. I will get everything I want,

and they will be destroyed forever. June will lose [custody of the

son]...and Michael's career will be over."

"Does that help [the boy]?" Schwartz asked.

"That's irrelevant to me," Chandler replied. "It's going to be bigger

than all of us put together. The whole thing is going to crash down on

everybody and destroy everybody in sight. It will be a massacre if I

don't get what I want."

Instead of going to the police, seemingly the most appropriate action

in a situation involving suspected child molestation, Chandler had

turned to a lawyer. And not just any lawyer. He'd turned to Barry

Rothman.

"This attorney I found, I picked the nastiest son of a bitch I could

find," Chandler said in the recorded conversation with Schwartz. "All

he wants to do is get this out in the public as fast as he can, as big

as he can, and humiliate as many people as he can. He's nasty, he's

mean, he's very smart, and he's hungry for the publicity." (Through

his attorney, Wylie Aitken, Rothman declined to be interviewed for

this article. Aitken agreed to answer general questions limited to the

Jackson case, and then only about aspects that did not involve

Chandler or the boy.)

To know Rothman, says a former colleague who worked with him during

the Jackson case, and who kept a diary of what Rothman and Chandler

said and did in Rothman's office, is to believe that Barry could have

"devised this whole plan, period. This [making allegations against

Michael Jackson] is within the boundary of his character, to do

something like this." Information supplied by Rothman's former

clients, associates and employees reveals a pattern of manipulation

and deceit.

Rothman has a general-law practice in Century City. At one time, he

negotiated music and concert deals for Little Richard, the Rolling

Stones, the Who, ELO and Ozzy Osbourne. Gold and platinum records

commemorating those days still hang on the walls of his office. With

his grayish-white beard and perpetual tan -- which he maintains in a

tanning bed at his house -- Rothman reminds a former client of "a

leprechaun." To a former employee, Rothman is "a demon" with "a

terrible temper." His most cherished possession, acquaintances say, is

his 1977 Rolls-Royce Corniche, which carries the license plate "BKR

1."

Over the years, Rothman has made so many enemies that his ex-wife once

expressed, to her attorney, surprise that someone "hadn't done him

in." He has a reputation for stiffing people. "He appears to be a

professional deadbeat... He pays almost no one," investigator Ed

Marcus concluded (in a report filed in Los Angeles Superior Court, as

part of a lawsuit against Rothman), after reviewing the attorney's

credit profile, which listed more than thirty creditors and judgment

holders who were chasing him. In addition, more than twenty civil

lawsuits involving Rothman have been filed in Superior Court, several

complaints have been made to the Labor Commission and disciplinary

actions for three incidents have been taken against him by the state

bar of California. In 1992, he was suspended for a year, though that

suspension was stayed and he was instead placed on probation for the

term.

In 1987, Rothman was $16,800 behind in alimony and child-support

payments. Through her attorney, his ex-wife, Joanne Ward, threatened

to attach Rothman's assets, but he agreed to make good on the debt. A

year later, after Rothman still hadn't made the payments, Ward's

attorney tried to put a lien on Rothman's expensive Sherman Oaks home.

To their surprise, Rothman said he no longer owned the house; three

years earlier, he'd deeded the property to Tinoa Operations, Inc., a

Panamanian shell corporation. According to Ward's lawyer, Rothman

claimed that he'd had $200,000 of Tinoa's money, in cash, at his house

one night when he was robbed at gunpoint. The only way he could make

good on the loss was to deed his home to Tinoa, he told them. Ward and

her attorney suspected the whole scenario was a ruse, but they could

never prove it. It was only after sheriff's deputies had towed away

Rothman's Rolls Royce that he began paying what he owed.

Documents filed with Los Angeles Superior Court seem to confirm the

suspicions of Ward and her attorney. These show that Rothman created

an elaborate network of foreign bank accounts and shell companies,

seemingly to conceal some of his assets -- in particular, his home and

much of the $531,000 proceeds from its eventual sale, in 1989. The

companies, including Tinoa, can be traced to Rothman. He bought a

Panamanian shelf company (an existing but nonoperating firm) and

arranged matters so that though his name would not appear on the list

of its officers, he would have unconditional power of attorney, in

effect leaving him in control of moving money in and out.

Meanwhile, Rothman's employees didn't fare much better than his

ex-wife. Former employees say they sometimes had to beg for their

paychecks. And sometimes the checks that they did get would bounce. He

couldn't keep legal secretaries. "He'd demean and humiliate them,"

says one. Temporary workers fared the worst. "He would work them for

two weeks," adds the legal secretary, "then run them off by yelling at

them and saying they were stupid. Then he'd tell the agency he was

dissatisfied with the temp and wouldn't pay." Some agencies finally

got wise and made Rothman pay cash up front before they'd do business

with him.

The state bar's 1992 disciplining of Rothman grew out of a

conflict-of-interest matter. A year earlier, Rothman had been kicked

off a case by a client, Muriel Metcalf, whom he'd been representing in

child-support and custody proceedings; Metcalf later accused him of

padding her bill. Four months after Metcalf fired him, Rothman,

without notifying her, began representing the company of her estranged

companion, Bob Brutzman.

The case is revealing for another reason: It shows that Rothman had

some experience dealing with child-molestation allegations before the

Jackson scandal. Metcalf, while Rothman was still representing her,

had accused Brutzman of molesting their child (which Brutzman denied).

Rothman's knowledge of Metcalf's charges didn't prevent him from going

to work for Brutzman's company -- a move for which he was disciplined.

By 1992, Rothman was running from numerous creditors. Folb Management,

a corporate real-estate agency, was one. Rothman owed the company

$53,000 in back rent and interest for an office on Sunset Boulevard.

Folb sued. Rothman then countersued, claiming that the building's

security was so inadequate that burglars were able to steal more than

$6,900 worth of equipment from his office one night. In the course of

the proceedings, Folb's lawyer told the court, "Mr. Rothman is not the

kind of person whose word can be taken at face value."

In November 1992, Rothman had his law firm file for bankruptcy,

listing thirteen creditors -- including Folb Management -- with debts

totaling $880,000 and no acknowledged assets. After reviewing the

bankruptcy papers, an ex-client whom Rothman was suing for $400,000 in

legal fees noticed that Rothman had failed to list a $133,000 asset.

The former client threatened to expose Rothman for "defrauding his

creditors" -- a felony -- if he didn't drop the lawsuit. Cornered,

Rothman had the suit dismissed in a matter of hours.

Six months before filing for bankruptcy, Rothman had transferred title

on his Rolls-Royce to Majo, a fictitious company he controlled. Three

years earlier, Rothman had claimed a different corporate owner for the

car -- Longridge Estates, a subsidiary of Tinoa Operations, the

company that held the deed to his home. On corporation papers filed by

Rothman, the addresses listed for Longridge and Tinoa were the same,

1554 Cahuenga Boulevard -- which, as it turns out, is that of a

Chinese restaurant in Hollywood.

It was with this man, in June 1993, that Evan Chandler began carrying

out the "certain plan" to which he referred in his taped conversation

with Dave Schwartz. At a graduation that month, Chandler confronted

his ex-wife with his suspicions. "She thought the whole thing was

baloney," says her ex-attorney, Michael Freeman. She told Chandler

that she planned to take their son out of school in the fall so they

could accompany Jackson on his "Dangerous" world tour. Chandler became

irate and, say several sources, threatened to go public with the

evidence he claimed he had on Jackson. "What parent in his right mind

would want to drag his child into the public spotlight?" asks Freeman.

"If something like this actually occurred, you'd want to protect your

child."

Jackson asked his then-lawyer, Bert Fields, to intervene. One of the

most prominent attorneys in the entertainment industry, Fields has

been representing Jackson since 1990 and had negotiated for him, with

Sony, the biggest music deal ever -- with possible earnings of $700

million. Fields brought in investigator Anthony Pellicano to help sort

things out. Pellicano does things Sicilian-style, being fiercely loyal

to those he likes but a ruthless hardball player when it comes to his

enemies.

On July 9, 1993, Dave Schwartz and June Chandler Schwartz played the

taped conversation for Pellicano. "After listening to the tape for ten

minutes, I knew it was about extortion," says Pellicano. That same

day, he drove to Jackson's Century City condominium, where Chandler's

son and the boy's half-sister were visiting. Without Jackson there,

Pellicano "made eye contact" with the boy and asked him, he says,

"very pointed questions": "Has Michael ever touched you? Have you ever

seen him naked in bed?" The answer to all the questions was no. The

boy repeatedly denied that anything bad had happened. On July 11,

after Jackson had declined to meet with Chandler, the boy's father and

Rothman went ahead with another part of the plan -- they needed to get

custody of the boy. Chandler asked his ex-wife to let the youth stay

with him for a "one-week visitation period." As Bert Fields later said

in an affidavit to the court, June Chandler Schwartz allowed the boy

to go based on Rothman's assurance to Fields that her son would come

back to her after the specified time, never guessing that Rothman's

word would be worthless and that Chandler would not return their son.

Wylie Aitken, Rothman's attorney, claims that "at the time [Rothman]

gave his word, it was his intention to have the boy returned."

However, once "he learned that the boy would be whisked out of the

country [to go on tour with Jackson], I don't think Mr. Rothman had

any other choice." But the chronology clearly indicates that Chandler

had learned in June, at the graduation, that the boy's mother planned

to take her son on the tour. The taped telephone conversation made in

early July, before Chandler took custody of his son, also seems to

verify that Chandler and Rothman had no intention of abiding by the

visitation agreement. "They [the boy and his mother] don't know it

yet," Chandler told Schwartz, "but they aren't going anywhere."

On July 12, one day after Chandler took control of his son, he had his

ex-wife sign a document prepared by Rothman that prevented her from

taking the youth out of Los Angeles County. This meant the boy would

be unable to accompany Jackson on the tour. His mother told the court

she signed the document under duress. Chandler, she said in an

affidavit, had threatened that "I would not have [the boy] returned to

me." A bitter custody battle ensued, making even murkier any charges

Chandler made about wrong-doing on Jackson's part. (As of this August

[1994], the boy was still living with Chandler.) It was during the

first few weeks after Chandler took control of his son -- who was now

isolated from his friends, mother and stepfather -- that the boy's

allegations began to take shape.

At the same time, Rothman, seeking an expert's opinion to help

establish the allegations against Jackson, called Dr. Mathis Abrams, a

Beverly Hills psychiatrist. Over the telephone, Rothman presented

Abrams with a hypothetical situation. In reply and without having met

either Chandler or his son, Abrams on July 15 sent Rothman a two-page

letter in which he stated that "reasonable suspicion would exist that

sexual abuse may have occurred." Importantly, he also stated that if

this were a real and not a hypothetical case, he would be required by

law to report the matter to the Los Angeles County Department of

Children's Services (DCS).

According to a July 27 entry in the diary kept by Rothman's former

colleague, it's clear that Rothman was guiding Chandler in the plan.

"Rothman wrote letter to Chandler advising him how to report child

abuse without liability to parent," the entry reads.

At this point, there still had been made no demands or formal

accusations, only veiled assertions that had become intertwined with a

fierce custody battle. On August 4, 1993, however, things became very

clear. Chandler and his son met with Jackson and Pellicano in a suite

at the Westwood Marquis Hotel. On seeing Jackson, says Pellicano,

Chandler gave the singer an affectionate hug (a gesture, some say,

that would seem to belie the dentist's suspicions that Jackson had

molested his son), then reached into his pocket, pulled out Abrams's

letter and began reading passages from it. When Chandler got to the

parts about child molestation, the boy, says Pellicano, put his head

down and then looked up at Jackson with a surprised expression, as if

to say "I didn't say that." As the meeting broke up, Chandler pointed

his finger at Jackson, says Pellicano, and warned "I'm going to ruin

you."

At a meeting with Pellicano in Rothman's office later that evening,

Chandler and Rothman made their demand - $20 million.

On August 13, there was another meeting in Rothman's office. Pellicano

came back with a counteroffer -- a $350,000 screenwriting deal.

Pellicano says he made the offer as a way to resolve the custody

dispute and give Chandler an opportunity to spend more time with his

son by working on a screenplay together. Chandler rejected the offer.

Rothman made a counterdemand -- a deal for three screenplays or

nothing -- which was spurned. In the diary of Rothman's ex-colleague,

an August 24 entry reveals Chandler's disappointment: "I almost had a

$20 million deal," he was overhear telling Rothman.

Before Chandler took control of his son, the only one making

allegations against Jackson was Chandler himself -- the boy had never

accused the singer of any wrongdoing. That changed one day in

Chandler's Beverly Hills dental office.

In the presence of Chandler and Mark Torbiner, a dental

anesthesiologist, the boy was administered the controversial drug

sodium Amytal -- which some mistakenly believe is a truth serum. And

it was after this session that the boy first made his charges against

Jackson. A newsman at KCBS-TV, in L.A., reported on May 3 of this year

that Chandler had used the drug on his son, but the dentist claimed he

did so only to pull his son's tooth and that while under the drug's

influence, the boy came out with allegations. Asked for this article

about his use of the drug on the boy, Torbiner replied: "If I used it,

it was for dental purposes."

Given the facts about sodium Amytal and a recent landmark case that

involved the drug, the boy's allegations, say several medical experts,

must be viewed as unreliable, if not highly questionable.

"It's a psychiatric medication that cannot be relied on to produce

fact," says Dr. Resnick, the Cleveland psychiatrist. "People are very

suggestible under it. People will say things under sodium Amytal that

are blatantly untrue." Sodium Amytal is a barbiturate, an invasive

drug that puts people in a hypnotic state when it's injected

intravenously. Primarily administered for the treatment of amnesia, it

first came into use during World War II, on soldiers traumatized --

some into catatonic states -- by the horrors of war. Scientific

studies done in 1952 debunked the drug as a truth serum and instead

demonstrated its risks: False memories can be easily implanted in

those under its influence. "It is quite possible to implant an idea

through the mere asking of a question," says Resnick. But its effects

are apparently even more insidious: "The idea can become their memory,

and studies have shown that even when you tell them the truth, they

will swear on a stack of Bibles that it happened," says Resnick.

Reply #1 posted 11/20/03 3:43pm

bananacologne

Recently, the reliability of the drug became an issue in a

high-profile trial in Napa County, California. After undergoing

numerous therapy sessions, at least one of which included the use of

sodium Amytal, 20-year-old Holly Ramona accused her father of

molesting her as a child. Gary Ramona vehemently denied the charge and

sued his daughter's therapist and the psychiatrist who had

administered the drug. This past May, jurors sided with Gary Ramona,

believing that the therapist and the psychiatrist may have reinforced

memories that were false. Gary Ramona's was the first successful legal

challenge to the so-called "repressed memory phenomenon" that has

produced thousands of sexual-abuse allegations over the past decade.

As for Chandler's story about using the drug to sedate his son during

a tooth extraction, that too seems dubious, in light of the drug's

customary use. "It's absolutely a psychiatric drug," says Dr. Kenneth

Gottlieb, a San Francisco psychiatrist who has administered sodium

Amytal to amnesia patients. Dr. John Yagiela, the coordinator of the

anesthesia and pain control department of UCLA's school of dentistry,

adds, "It's unusual for it to be used [for pulling a tooth]. It makes

no sense when better, safer alternatives are available. It would not

be my choice."

Because of sodium Amytal's potential side effects, some doctors will

administer it only in a hospital. "I would never want to use a drug

that tampers with a person's unconscious unless there was no other

drug available," says Gottlieb. "And I would not use it without

resuscitating equipment, in case of allergic reaction, and only with

an M.D. anesthesiologist present."

Chandler, it seems, did not follow these guidelines. He had the

procedure performed on his son in his office, and he relied on the

dental anesthesiologist Mark Torbiner for expertise. (It was Torbiner

who'd introduced Chandler and Rothman in 1991, when Rothman needed

dental work.)

The nature of Torbiner's practice appears to have made it highly

successful. "He boasts that he has $100 a month overhead and $40,000 a

month income," says Nylla Jones, a former patient of his. Torbiner

doesn't have an office for seeing patients; rather, he travels to

various dental offices around the city, where he administers

anesthesia during procedures.

This magazine has learned that the U.S. Drug Enforcement

Administration is probing another aspect of Torbiner's business

practices: He makes housecalls to administer drugs -- mostly morphine

and Demerol -- not only postoperatively to his dental patients but

also, it seems, to those suffering pain whose source has nothing to do

with dental work. He arrives at the homes of his clients -- some of

them celebrities -- carrying a kind of fishing-tackle box that

contains drugs and syringes. At one time, the license plate on his

Jaguar read "SLPYDOC." According to Jones, Torbiner charges $350 for a

basic ten-to-twenty-minute visit. In what Jones describes as standard

practice, when it's unclear how long Torbiner will need to stay, the

client, anticipating the stupor that will soon set in, leaves a blank

check for Torbiner to fill in with the appropriate amount.

Torbiner wasn't always successful. In 1989, he got caught in a lie and

was asked to resign from UCLA, where he was an assistant professor at

the school of dentistry. Torbiner had asked to take a half-day off so

he could observe a religious holiday but was later found to have

worked at a dental office instead.

A check of Torbiner's credentials with the Board of Dental Examiners

indicates that he is restricted by law to administering drugs solely

for dental-related procedures. But there is clear evidence that he has

not abided by those restrictions. In fact, on at least eight

occasions, Torbiner has given a general anesthetic to Barry Rothman,

during hair-transplant procedures. Though normally a local anesthetic

would be injected into the scalp, "Barry is so afraid of the pain,"

says Dr. James De Yarman, the San Diego physician who performed

Rothman's transplants, "that [he] wanted to be put out completely." De

Yarman said he was "amazed" to learn that Torbiner is a dentist,

having assumed all along that he was an M.D.

In another instance, Torbiner came to the home of Nylla Jones, she

says, and injected her with Demerol to help dull the pain that

followed her appendectomy.

On August 16, three days after Chandler and Rothman rejected the

$350,000 script deal, the situation came to a head. On behalf of June

Chandler Schwartz, Michael Freeman notified Rothman that he would be

filing papers early the next morning that would force Chandler to turn

over the boy. Reacting quickly, Chandler took his son to Mathis

Abrams, the psychiatrist who'd provided Rothman with his assessment of

the hypothetical child-abuse situation. During a three-hour session,

the boy alleged that Jackson had engaged in a sexual relationship with

him. He talked of masturbation, kissing, fondling of nipples and oral

sex. There was, however, no mention of actual penetration, which might

have been verified by a medical exam, thus providing corroborating

evidence.

The next step was inevitable. Abrams, who is required by law to report

any such accusation to authorities, called a social worker at the

Department of Children's Services, who in turn contacted the police.

The full-scale investigation of Michael Jackson was about to begin.

Five days after Abrams called the authorities, the media got wind of

the investigation. On Sunday morning, August 22, Don Ray, a free-lance

reporter in Burbank, was asleep when his phone rang. The caller, one

of his tipsters, said that warrants had been issued to search

Jackson's ranch and condominium. Ray sold the story to L.A.'s KNBC-TV,

which broke the news at 4 P.M. the following day.

After that, Ray "watched this story go away like a freight train," he

says. Within twenty-four hours, Jackson was the lead story on

seventy-three TV news broadcasts in the Los Angeles area alone and was

on the front page of every British newspaper. The story of Michael

Jackson and the 13-year-old boy became a frenzy of hype and

unsubstantiated rumor, with the line between tabloid and mainstream

media virtually eliminated.

The extent of the allegations against Jackson wasn't known until

August 25. A person inside the DCS illegally leaked a copy of the

abuse report to Diane Dimond of Hard Copy. Within hours, the L.A.

office of a British news service also got the report and began selling

copies to any reporter willing to pay $750. The following day, the

world knew about the graphic details in the leaked report. "While

laying next to each other in bed, Mr. Jackson put his hand under [the

child's] shorts," the social worker had written. From there, the

coverage soon demonstrated that anything about Jackson would be fair

game.

"Competition among news organizations became so fierce," says KNBC

reporter Conan Nolan, that "stories weren't being checked out. It was

very unfortunate." The National Enquirer put twenty reporters and

editors on the story. One team knocked on 500 doors in Brentwood

trying to find Evan Chandler and his son. Using property records, they

finally did, catching up with Chandler in his black Mercedes. "He was

not a happy man. But I was," said Andy O'Brien, a tabloid

photographer.

Next came the accusers -- Jackson's former employees. First, Stella

and Philippe Lemarque, Jackson' ex-housekeepers, tried to sell their

story to the tabloids with the help of broker Paul Barresi, a former

porn star. They asked for as much as half a million dollars but wound

up selling an interview to The Globe of Britain for $15,000. The

Quindoys, a Filipino couple who had worked at Neverland, followed.

When their asking price was $100,000, they said " 'the hand was

outside the kid's pants,' " Barresi told a producer of Frontline, a

PBS program. "As soon as their price went up to $500,000, the hand

went inside the pants. So come on." The L.A. district attorney's

office eventually concluded that both couples were useless as

witnesses.

Next came the bodyguards. Purporting to take the journalistic high

road, Hard Copy's Diane Dimond told Frontline in early November of

last year that her program was "pristinely clean on this. We paid no

money for this story at all." But two weeks later, as a Hard Copy

contract reveals, the show was negotiating a $100,000 payment to five

former Jackson security guards who were planning to file a $10 million

lawsuit alleging wrongful termination of their jobs.

On December 1, with the deal in place, two of the guards appeared on

the program; they had been fired, Dimond told viewers, because "they

knew too much about Michael Jackson's strange relationship with young

boys." In reality, as their depositions under oath three months later

reveal, it was clear they had never actually seen Jackson do anything

improper with Chandler's son or any other child:

"So you don't know anything about Mr. Jackson and [the boy], do you?"

one of Jackson's attorneys asked former security guard Morris Williams

under oath. "All I know is from the sworn documents that other people

have sworn to."

"But other than what someone else may have said, you have no firsthand

knowledge about Mr. Jackson and [the boy], do you?"

"That's correct."

"Have you spoken to a child who has ever told you that Mr. Jackson did

anything improper with the child?"

"No."

When asked by Jackson's attorney where he had gotten his impressions,

Williams replied: "Just what I've been hearing in the media and what

I've experienced with my own eyes."

"Okay. That's the point. You experienced nothing with your own eyes,

did you?"

"That's right, nothing."

(The guards' lawsuit, filed in March 1994, was still pending as this

article went to press.)

[NOTE: The case was thrown out of court in July 1995. Read the details

above..]

Next came the maid. On December 15, Hard Copy presented "The Bedroom

Maid's Painful Secret." Blanca Francia told Dimond and other reporters

that she had seen a naked Jackson taking showers and Jacuzzi baths

with young boys. She also told Dimond that she had witnessed her own

son in compromising positions with Jackson -- an allegation that the

grand juries apparently never found credible.

A copy of Francia's sworn testimony reveals that Hard Copy paid her

$20,000, and had Dimond checked out the woman's claims, she would have

found them to be false. Under deposition by a Jackson attorney,

Francia admitted she had never actually see Jackson shower with anyone

nor had she seen him naked with boys in his Jacuzzi. They always had

their swimming trunks on, she acknowledged.

The coverage, says Michael Levine, a Jackson press representative,

"followed a proctologist's view of the world. Hard Copy was loathsome.

The vicious and vile treatment of this man in the media was for

selfish reasons. [Even] if you have never bought a Michael Jackson

record in your life, you should be very concerned. Society is built on

very few pillars. One of them is truth. When you abandon that, it's a

slippery slope."

The investigation of Jackson, which by October 1993 would grow to

involve at least twelve detectives from Santa Barbara and Los Angeles

counties, was instigated in part by the perceptions of one

psychiatrist, Mathis Abrams, who had no particular expertise in child

sexual abuse. Abrams, the DCS caseworker's report noted, "feels the

child is telling the truth." In an era of widespread and often false

claims of child molestation, police and prosecutors have come to give

great weight to the testimony of psychiatrists, therapists and social

workers.

Police seized Jackson's telephone books during the raid on his

residences in August and questioned close to thirty children and their

families. Some, such as Brett Barnes and Wade Robson, said they had

shared Jackson's bed, but like all the others, they gave the same

response -- Jackson had done nothing wrong. "The evidence was very

good for us," says an attorney who worked on Jackson's defense. "The

other side had nothing but a big mouth."

Despite the scant evidence supporting their belief that Jackson was

guilty, the police stepped up their efforts. Two officers flew to the

Philippines to try to nail down the Quindoys' "hand in the pants"

story, but apparently decided it lacked credibility. The police also

employed aggressive investigative techniques -- including allegedly

telling lies -- to push the children into making accusations against

Jackson. According to several parents who complained to Bert Fields,

officers told them unequivocally that their children had been

molested, even though the children denied to their parents that

anything bad had happened. The police, Fields complained in a letter

to Los Angeles Police Chief Willie Williams, "have also frightened

youngsters with outrageous lies, such as 'We have nude photos of you.'

There are, of course, no such photos." One officer, Federico Sicard,

told attorney Michael Freeman that he had lied to the children he'd

interviewed and told them that he himself had been molested as a

child, says Freeman. Sicard did not respond to requests for an

interview for this article.

All along, June Chandler Schwartz rejected the charges Chandler was

making against Jackson -- until a meeting with police in late August

1993. Officers Sicard and Rosibel Ferrufino made a statement that

began to change her mind. "[The officers] admitted they only had one

boy," says Freeman, who attended the meeting, "but they said, 'We're

convinced Michael Jackson molested this boy because he fits the

classic profile of a pedophile perfectly.' "

"There's no such thing as a classic profile. They made a completely

foolish and illogical error," says Dr. Ralph Underwager, a Minneapolis

psychiatrist who has treated pedophiles and victims of incest since

1953. Jackson, he believes, "got nailed" because of "misconceptions

like these that have been allowed to parade as fact in an era of

hysteria." In truth, as a U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

study shows, many child-abuse allegations -- 48 percent of those filed

in 1990 -- proved to be unfounded.

"It was just a matter of time before someone like Jackson became a

target," says Phillip Resnick. "He's rich, bizarre, hangs around with

kids and there is a fragility to him. The atmosphere is such that an

accusation must mean it happened."

The seeds of settlement were already being sown as the police

investigation continued in both counties through the fall of 1993. And

a behind-the-scenes battle among Jackson's lawyers for control of the

case, which would ultimately alter the course the defense would take,

had begun.

By then, June Chandler Schwartz and Dave Schwartz had united with Evan

Chandler against Jackson. The boy's mother, say several sources,

feared what Chandler and Rothman might do if she didn't side with

them. She worried that they would try to advance a charge against her

of parental neglect for allowing her son to have sleepovers with

Jackson. Her attorney, Michael Freeman, in turn, resigned in disgust,

saying later that "the whole thing was such a mess. I felt

uncomfortable with Evan. He isn't a genuine person, and I sensed he

wasn't playing things straight."

Over the months, lawyers for both sides were retained, demoted and

ousted as they feuded over the best strategy to take. Rothman ceased

being Chandler's lawyer in late August, when the Jackson camp filed

extortion charges against the two. Both then hired high-priced

criminal defense attorneys to represent them.. (Rothman retained

Robert Shapiro, now O.J. Simpson's chief lawyer.) According to the

diary kept by Rothman's former colleague, on August 26, before the

extortion charges were filed, Chandler was heard to say "It's my ass

that's on the line and in danger of going to prison." The

investigation into the extortion charges was superficial because, says

a source, "the police never took it that seriously. But a whole lot

more could have been done." For example, as they had done with

Jackson, the police could have sought warrants to search the homes and

offices of Rothman and Chandler. And when both men, through their

attorneys, declined to be interviewed by police, a grand jury could

have been convened.

In mid-September, Larry Feldman, a civil attorney who'd served as head

of the Los Angeles Trial Lawyers Association, began representing

Chandler's son and immediately took control of the situation. He filed

a $30 million civil lawsuit against Jackson, which would prove to be

the beginning of the end.

Once news of the suit spread, the wolves began lining up at the door.

According to a member of Jackson's legal team, "Feldman got dozens of

letters from all kinds of people saying they'd been molested by

Jackson. They went through all of them trying to find somebody, and

they found zero."

With the possibility of criminal charges against Jackson now looming,

Bert Fields brought in Howard Weitzman, a well-known criminal-defense

lawyer with a string of high-profile clients -- including John

DeLorean, whose trail he won, and Kim Basinger, whose Boxing Helena

contract dispute he lost. (Also, for a short time this June, Weitzman

was O.J. Simpson's attorney.) Some predicted a problem between the two

lawyers early on. There wasn't room for two strong attorneys used to

running their own show.

From the day Weitzman joined Jackson's defense team, "he was talking

settlement," says Bonnie Ezkenazi, an attorney who worked for the

defense. With Fields and Pellicano still in control of Jackson's

defense, they adopted an aggressive strategy. They believed staunchly

in Jackson's innocence and vowed to fight the charges in court.

Pellicano began gathering evidence to use in the trial, which was

scheduled for March 21, 1994. "They had a very weak case," says

Fields. "We wanted to fight. Michael wanted to fight and go through a

trial. We felt we could win."

Dissension within the Jackson camp accelerated on November 12, after

Jackson's publicist announced at a press conference that the singer

was canceling the remainder of his world tour to go into a

drug-rehabilitation program to treat his addiction to painkillers.

Fields later told reporters that Jackson was "barely able to function

adequately on an intellectual level." Others in Jackson's camp felt it

was a mistake to portray the singer as incompetent. "It was

important," Fields says, "to tell the truth. [Larry] Feldman and the

press took the position that Michael was trying to hide and that it

was all a scam. But it wasn't."

On November 23, the friction peaked. Based on information he says he

got from Weitzman, Fields told a courtroom full of reporters that a

criminal indictment against Jackson seemed imminent. Fields had a

reason for making the statement: He was trying to delay the boy's

civil suit by establishing that there was an impending criminal case

that should be tried first. Outside the courtroom, reporters asked why

Fields had made the announcement, to which Weitzman replied

essentially that Fields "misspoke himself." The comment infuriated

Fields, "because it wasn't true," he says. "It was just an outrage. I

was very upset with Howard." Fields sent a letter of resignation to

Jackson the following week.

"There was this vast group of people all wanting to do a different

thing, and it was like moving through molasses to get a decision,"

says Fields. "It was a nightmare, and I wanted to get the hell out of

it." Pellicano, who had received his share of flak for his aggressive

manner, resigned at the same time.

With Fields and Pellicano gone, Weitzman brought in Johnnie Cochran

Jr., a well-known civil attorney who is now helping defend O.J.

Simpson. And John Branca, whom Fields had replaced as Jackson's

general counsel in 1990, was back on board. In late 1993, as DAs in

both Santa Barbara and Los Angeles counties convened grand juries to

assess whether criminal charges should be filed against Jackson, the

defense strategy changed course and talk of settling the civil case

began in earnest, even though his new team also believed in Jackson's

innocence.

Why would Jackson's side agree to settle out of court, given his

claims of innocence and the questionable evidence against him? His

attorneys apparently decided there were many factors that argued

against taking the case to civil court. Among them was the fact that

Jackson's emotional fragility would be tested by the oppressive media

coverage that would likely plague the singer day after day during a

trial that could last as long as six months. Politics and racial

issues had also seeped into legal proceedings -- particularly in Los

Angeles, which was still recovering from the Rodney King ordeal -- and

the defense feared that a court of law could not be counted on to

deliver justice. Then, too, there was the jury mix to consider. As one

attorney says, "They figured that Hispanics might resent [Jackson] for

his money, blacks might resent him for trying to be white, and whites

would have trouble getting around the molestation issue." In Resnick's

opinion, "The hysteria is so great and the stigma [of child

molestation] is so strong, there is no defense against it."

Jackson's lawyers also worried about what might happen if a criminal

trial followed, particularly in Santa Barbara, which is a largely

white, conservative, middle-to-upper-class community. Any way the

defense looked at it, a civil trial seemed too big a gamble. By

meeting the terms of a civil settlement, sources say, the lawyers

figured they could forestall a criminal trial through a tacit

understanding that Chandler would agree to make his son unavailable to

testify.

Others close to the case say the decision to settle also probably had

to do with another factor -- the lawyers' reputations. "Can you

imagine what would happen to an attorney who lost the Michael Jackson

case?" says Anthony Pellicano. "There's no way for all three lawyers

to come out winners unless they settle. The only person who lost is

Michael Jackson." But Jackson, says Branca, "changed his mind about

[taking the case to trial] when he returned to this country. He hadn't

seen the massive coverage and how hostile it was. He just wanted the

whole thing to go away."

On the other side, relationships among members of the boy's family had

become bitter. During a meeting in Larry Feldman's office in late

1993, Chandler, a source says, "completely lost it and beat up Dave

[Schwartz]." Schwartz, having separated from June by this time, was

getting pushed out of making decisions that affected his stepson, and

he resented Chandler for taking the boy and not returning him.

"Dave got mad and told Evan this was all about extortion, anyway, at

which point Evan stood up, walked over and started hitting Dave," a

second source says.

To anyone who lived in Los Angeles in January 1994, there were two

main topics of discussion -- the earthquake and the Jackson

settlement. On January 25, Jackson agreed to pay the boy an

undisclosed sum. The day before, Jackson's attorneys had withdrawn the

extortion charges against Chandler and Rothman.

The actual amount of the settlement has never been revealed, although

speculation has placed the sum around $20 million. One source says

Chandler and June Chandler Schwartz received up to $2 million each,

while attorney Feldman might have gotten up to 25 percent in

contingency fees. The rest of the money is being held in trust for the

boy and will be paid out under the supervision of a court-appointed

trustee.

"Remember, this case was always about money," Pellicano says, "and

Evan Chandler wound up getting what he wanted." Since Chandler still

has custody of his son, sources contend that logically this means the

father has access to any money his son gets.

By late May 1994, Chandler finally appeared to be out of dentistry.

He'd closed down his Beverly Hills office, citing ongoing harassment

from Jackson supporters. Under the terms of the settlement, Chandler

is apparently prohibited from writing about the affair, but his

brother, Ray Charmatz, was reportedly trying to get a book deal.

In what may turn out to be the never-ending case, this past August,

both Barry Rothman and Dave Schwartz (two principal players left out

of the settlement) filed civil suits against Jackson. Schwartz

maintains that the singer broke up his family. Rothman's lawsuit

claims defamation and slander on the part of Jackson, as well as his

original defense team -- Fields, Pellicano and Weitzman -- for the

allegations of extortion. "The charge of [extortion]," says Rothman

attorney Aitken, "is totally untrue. Mr. Rothman has been held up for

public ridicule, was the subject of a criminal investigation and

suffered loss of income." (Presumably, some of Rothman's lost income

is the hefty fee he would have received had he been able to continue

as Chandler's attorney through the settlement phase.)

As for Michael Jackson, "he is getting on with his life," says

publicist Michael Levine. Now married, Jackson also recently recorded

three new songs for a greatest-hits album and completed a new music

video called "History."

And what became of the massive investigation of Jackson? After

millions of dollars were spent by prosecutors and police departments

in two jurisdictions, and after two grand juries questioned close to

200 witnesses, including 30 children who knew Jackson, not a single

corroborating witness could be found. (In June 1994, still determined

to find even one corroborating witness, three prosecutors and two

police detectives flew to Australia to again question Wade Robson, the

boy who had acknowledged that he'd slept in the same bed with Jackson.

Once again, the boy said that nothing bad had happened.)

The sole allegations leveled against Jackson, then, remain those made

by one youth, and only after the boy had been give a potent hypnotic

drug, leaving him susceptible to the power of suggestion.

"I found the case suspicious," says Dr. Underwager, the Minneapolis

psychiatrist, "precisely because the only evidence came from one boy.

That would be highly unlikely. Actual pedophiles have an average of

240 victims in their lifetime. It's a progressive disorder. They're

never satisfied."

Given the slim evidence against Jackson, it seems unlikely he would

have been found guilty had the case gone to trial. But in the court of

public opinion, there are no restrictions. People are free to

speculate as they wish, and Jackson's eccentricity leaves him

vulnerable to the likelihood that the public has assumed the worst

about him.

So is it possible that Jackson committed no crime -- that he is what

he has always purported to be, a protector and not a molester of

children? Attorney Michael Freeman thinks so: "It's my feeling that

Jackson did nothing wrong and these people [Chandler and Rothman] saw

an opportunity and programmed it. I believe it was all about money."

To some observers, the Michael Jackson story illustrates the dangerous

power of accusation, against which there is often no defense --

particularly when the accusations involve child sexual abuse. To

others, something else is clear now -- that police and prosecutors

spent millions of dollars to create a case whose foundation never

existed.

Mary A Fischer is a GQ senior writer based in Los Angeles.

Edited by Arcoiris - 14/9/2014, 20:08

|

|

Contacts

Contacts